Month: December 2023

And people of Colors. My brothers fetishize me too, Emulate, Imitate, in rhythm my soul kaleidoscoped. Some say it is a strange bag, a drag, A drag that I represent the other colors of the American Flag One hundred precent cotton icon, with an invisible price tag .

The price of being oneself in America.

Salih Michael Fisher.

On October 29, 2016, I took a visit to Northwestern University’s Block Museum in Evanston, Illinois. It was a brisk fall day. My partner and I walked through the expansive and absolutely beautiful campus towards the museum. The bright purple neon sign lead us to the second floor to the Keep the Shadow, Ere the Substance Fade exhibition by C.C. McKee. In a small room in the corner of larger gallery space was full of images from Queer artists that lived, loved, and died during the HIV/Aids crisis in the 1980’s (find a more detailed timeline click here). Among the artists featured there was Etienne, born Domingo Orejudos. If you are familiar with Etienne’s work, or if you are just stumbling upon it, Etienne has an incredible and important story as an artist, Leatherman, and man of color.

My name is Erica Beatrix Brooks. I am a School of the Art Institute Masters graduate, artist, Queer identified woman of color. During my time at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I wrote my thesis, Part of the Party. Part of the Party investigated the experiences of Walter Houston III and The Onyx Brotherhood. The Onyx Brotherhood is one of the largest Leather groups for Black men in the country. ( Find out more about them here🙂 Through this work I explored the subject of race in Leather culture in Chicago. When I began my research, I encountered the struggle of finding information about men of color in Leather. Leather communities, histories, and stories of Leathermen of color are buried amongst informational how-to guides for Bondage and Leatherwear, explorations of sex and relationships usually from the perspective of White individuals in Leather. This lack archived experiences and stories of men of color in Leather made it difficult to work on my thesis. This same lack of information has made it even more difficult to find any information about Etienne as a man and artist of color.

My inspiration for Part of the Party was Etienne and his art. Artists have multiple aspects to their personality. An artist’s work can represent those aspects openly or more covertly. In my personal life as an artist, for a long time I avoided talking about my identity as a Black Queer woman. I feared that my identity would overpower the technical skill of my work. As I began to grow as an artist, I began creating work about race, gender, and Queer identity. Many other Black artists have investigated race in their work, but there are also artists of color that rarely explore identity. Etienne is an example of this type of artist. Through this digital exhibition I will critically explore a few different subjects:

- How is race discussed in Leather communities in a broader sense?

- How do men of color in Leather Communities talk about their racial identities?

- Why did Etienne rarely or if ever talk about his experience as a man of color in leather?

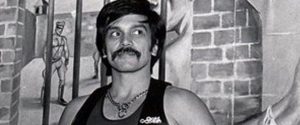

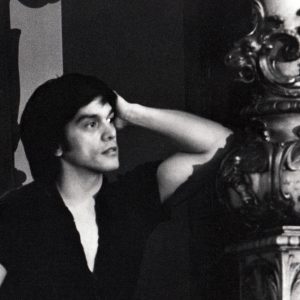

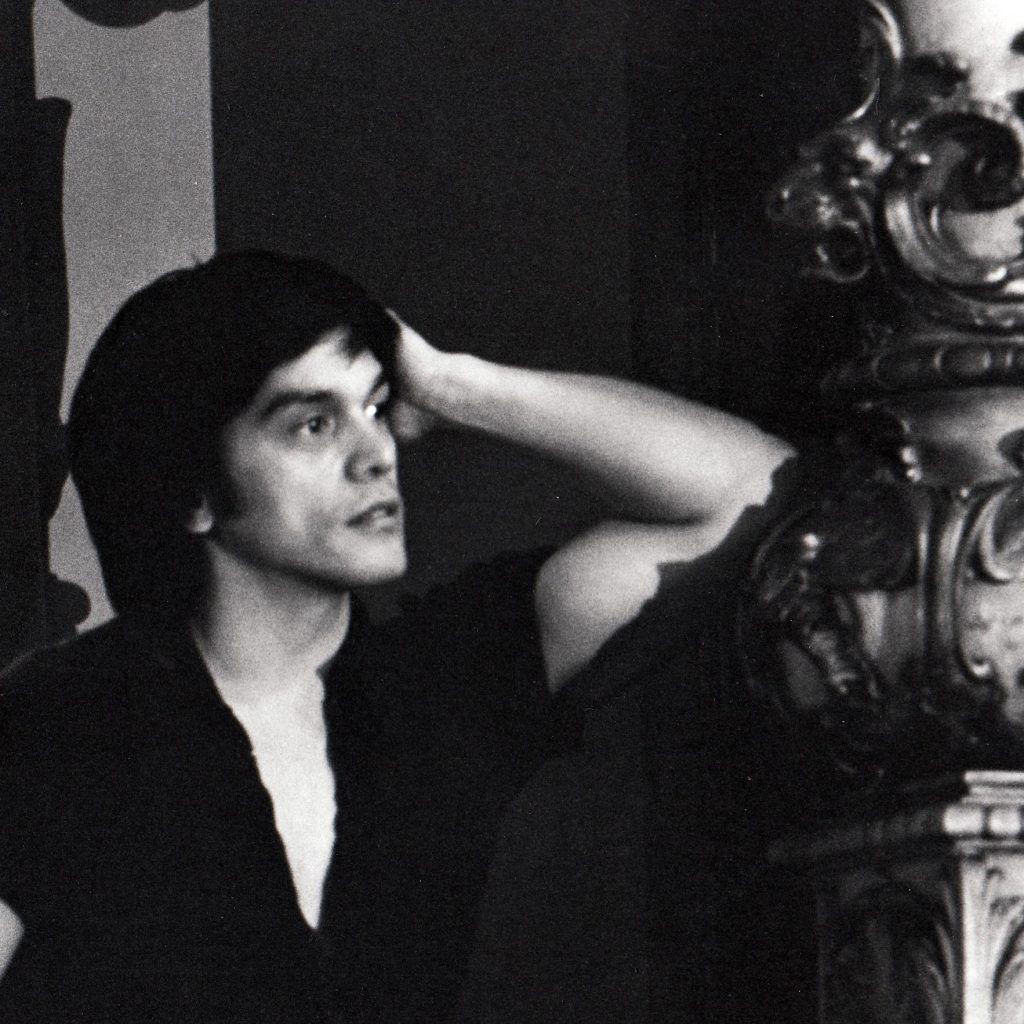

Domingo Orejudos. Dom. Etienne.

As I began writing this digital exhibition, I had some background information on Etienne’s art , but not very much on his personality or what he was like as an individual. Was he quiet and shy? Did he light up a room when he entered? Did he drink coffee or tea when he painted? Did he think his artwork would impact anyone at all? Lee Law, a patron of the historical Gold Coast Leather Bar talks about Etienne in this quote:

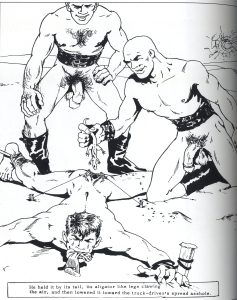

Lee Law recalled a conversation there with Orejudos and another man during which the other man went on at great length about what great art the Gold Coast paintings were. Orejudos finally broke in with, ‘That’s not art. They’re jack-off pictures’.

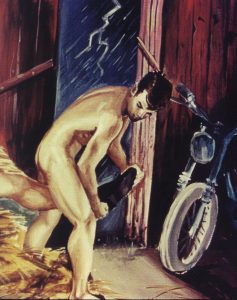

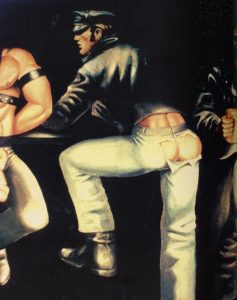

Reading this quote and comparing his artwork to this description of Etienne, it is similar to putting a jigsaw puzzle together, but one of the pieces is missing. This description of Etienne would partially explain why his work never explored racial identity. Most of his characters in his painting were White men portrayed as heroic, strong, taking on both dominant and submissive roles, and his interpretation of ultimate symbol of sexuality and desire. Etienne talks more about his sexual attraction was the creative inspiration for his work in this quote found on the Leather Archives website:

By his teens he drew to arouse himself, and his first orgasms came from drawing what he termed “dirty pictures,” which he would then burn once they got him off. Shortly after meeting Chuck Renslow, Dom had the opportunity to publish some of his erotic drawings in the magazine “Tomorrow’s Man.” Close to publication date, Dom realized he wasn’t ready to go that public and asked the publisher if he could use a different name. The publisher agreed, but said the new name had to be the same number of letters as the name “Domingo,” which had already been typeset. Dom had recently read a book featuring a character whose name contained the right number of letters: Etienne. Later in his career, Dom/Etienne remarked that he wished he had chosen a more aggressively masculine name to attach to his art.

As I synthesize this quote, secrecy and protection of his sexuality and identity were very important to Etienne. His work seems to act as a mask for him. Even his desire to go back and change his name to a more masculine name provides deep insight to his relationship to his art and sexual identity, but not his racial identity. Did Etienne equate masculinity with White men, or did he want to reflect his sexual attraction in his work?

The Keep the Shadow, Ere the Substance Fade exhibition talked about Etienne’s exploration of sexuality in one of Etienne’s paintings:

From the late 1970’s [this painting] takes up two popular uniform fetishes and revels in [a] casual erotic encounter indicated not only by the lack of a condom, but also the prominent jar of Vaseline, a lubricant that would be abandoned during the AIDS crisis because the oil-based product destroyed latex prophylactics. Such encounters were actively discouraged with the mergence of HIV.

Much of Etienne’s work shows the depth and immediacy of human desire that counteracted the protection and sterilization of sex for Gay men in the 1980’s. Before the 80’s, Gay men were beginning to openly express their homosexuality. With the wave of HIV/AIDS related illnesses and death, made Gay men and the Gay identity once again a source of hatred, fear, and discrimination.

Since there is little record of any conversations of Etienne reflecting on his racial identity, I have been looking at the stories of other Men in color in Leather. Some of the articles and books I have read describe being a man of color in Leather as the equivalent of being a minority with a minority. Or as I have framed it being “inside the closet’s closet.”

The term “in the closet”has had a few different meanings over the years. When I think of the term, I think about celebrities, some of my friends talking to their parents and loved ones, and the question “Did you come out of the closet?” An article on theweek.com explains one of the most common understandings of the coming out process:

“Coming out,” however, has long been used in the gay community, but it first meant something different than it does now. “A gay man’s coming out originally referred to his being formally presented to the largest collective manifestation of prewar gay society, the enormous drag balls that were patterned on the debutante and masquerade balls of the dominant culture and were regularly held in New York, Chicago, New Orleans, Baltimore, and other cities.” The phrase “coming out” did not refer to coming out of hiding, but to joining into a society of peers. The phrase was borrowed from the world of debutante balls, where young women “came out” in being officially introduced to society.”

There was one question that permeated almost every discussion I have had about Queer and LGBTQ identity: Does an individual have to “come out of the closet” and talk about their Gay identity openly. Straight identified people are not expected to reveal their sexuality in the same way LGBTQ identified people are expected to reveal their sexual orientation. The same article also talks about the idea that I bring up with the idea of coming of a layer of “closets”:

“The gay debutante balls were a matter of public record and often covered in the newspaper, so “coming out” within gay society often meant revealing your sexual orientation in the wider society as well, but the phrase didn’t necessarily carry the implication that if you hadn’t yet come out, you were keeping it a secret. There were other metaphors for the act of hiding or revealing homosexuality. Gay people could “wear a mask” or “take off the mask.” A man could “wear his hair up” or “let his hair down,” or “drop hairpins” that would only be recognized by other gay men.”

Views of homosexuality, sexual identity, and being out changed drastically through the course of Etienne’s life and will have likely to have had an impact on what Etienne shared through his work. Much of Gay male and Leather culture that we know of now was formed after World War II. Men in the military could bond and be with other men without fear of being “outed”. Military uniforms are the model and inspiration for outfit uniformity found in Leather groups. Since Etienne was born in 1933, he lived through some of the most important times in Queer history: Stonewall, AIDS and HIV, decades long discrimination against Queer individuals, and homosexuality being classified as a mental illness.

Find a longer timeline here .

In 1984, Geoff Mains wrote the pivotal book,Urban Aboriginals. This book was an in-depth look into the world of Gay men in Leather communities. Often Gay and Leather communities are lumped together and it is assumed that all homosexual men are part of Leather communities. Because of the change in the wider understandings of homosexuality, the uniform for Gay men became more varied and less focused on a unified look. Before World War II, military uniforms would mask homosexuality and allow Gay men to keep their identity private. In the 1980’s, the homosexual identity and visual markers for homosexuals was much more mainstream.

Almost two decades later, Cain Berlinger, a Black gay man in Leather, wrote the book Black Men in Leather. Urban Aboriginals talked about intersections of gay and Leather identities, but included nothing about race, women, and transgender identified individuals in Leather communities. Berlinger wanted to close the racial gap in literature on Black Leather communities. Black Men in Leather was a larger interview project that asked Black gay men in Leather about their experiences. Through his interviews Berlinger found that many Black men did not want to talk about their experiences openly:

“ It was difficult to reach many MOC and MOCL. Many of those polled were not in the Leather Community, and others were unaware of the need for their participation. Used to being ignored and convinced their concerns counted for nothing, many MOC simply ignored the calls for submissions, while others questioned the value of having their view seen at all.”

Intersectionality and Subcultures

In 2014, I was introduced to the word intersectionality. Often in academic environments, there are worlds that seem so out of touch with common vernacular. Intersectionality was hard to put a simple definition and understanding on. Intersectionality is described as:

[A] term first coined in 1989 by American civil rights advocate and leading scholar of critical race theory, Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw. It is the study of overlapping or intersecting social identities and related systems of oppression, domination, or discrimination. The theory suggests that—and seeks to examine how—various biological, social and cultural categories such as gender, race, class, ability, sexual orientation, religion, caste, age, nationality and other sectarian axes of identity interact on multiple and often simultaneous levels.

Although the word intersectionality has a date of creation, the idea has had a huge impact on my life long before I heard the term. As a Black Queer woman, these identities are a constant reminder of my ranking in U.S. and globally. As a Black person, I face race based discrimination, as a cis-gendered women I face gender based discrimination, and a queer person I face sexual discrimination. Also it is a tough reality, my identity is special and makes my experiences in the U.S. unique. This pride and sense of community I and many people with intersecting identities feel can be described as a subculture. Mains talks about subculture in this quote:

“(Subculture ) provides its members with self identification as a group. It provides a network within which individuals focus their primary relationships. And most importantly, it creates a prism through which they are able to refract larger cultural values in terms of their own experience.”

Mains talks more about the Leather identity specifically:

“Leathermen live their lives in a form of mental isolation from the mainstream of society that has been maintained by stigma. An almost universal condemnation of leather sex, more commonly understood only as sado-masochism , raises a barrier about their social life, companionships, and expectations. It does so in much the same way that Gay and non Gay experiences have long be separated. Leathermen may don business suits and partake of the larger world, sometimes on the proviso that they downplay those parts of their lives that society deems unacceptable, but mote usually on the basis that they remain silent.”

Mains does a fantastic job explaining how intersecting identities are viewed and expressed in different parts of larger society. The same way military uniforms disguised homosexuality, business suits cloak Leather fantasies, identities, and communities. Although White Gay men may be able to “blind in” and hide their identity, for many people of color, the skin can not be easily disguised with an outfit. Race is one of the most visual parts of our human identity and unlike homosexuality and racial identity cannot be readily hidden. Berlinger interviewed many Black men about their intersecting identity especially their Black and Leather identities. Berlinger talks about his own experiences:

“As a Black man in Leather, I found the safest refuge was in the community that I felt sometimes only saw me as a super-stud with an enormous endowment who fornicated all night long. Cloaked in what many White men see as an innocent sexual myth… Let’s not forget that the community is ‘accepting’. There is however, little room for intellectual maneuverability when you have to be either funny or sexual to survive, like functioning in a cultural prison.”

This quotes makes me wonder: Did Etienne fear being in a cultural prison as a Leatherman of color and as an artist of color? Since he is not Black or White, did he navigate the leather community differently? I also think back to Etienne’s sexualization of White men in his work. If I compare that fact to what Berlinger says about being trapped in a cultural prison, I wonder if Etienne wanted to turn the table and fetishize the White male body.

At this point, I want to let the questions and information about Etienne linger in your mind . In closing, I have a few more questions for you as a reader.

- Is it necessary for and artist of color to show their racial identity in their work?

- Do you think Etienne avoided deep conversations about race and gay identity as a way to focus on artistic strength of the work and not the ideas behind it?

- How would Etienne’s work been received it he only featured men of color in his work?

As I leave you with those questions, I want to thank you for your time and encourage you to learn more about Etienne.

Thank you,

Erica Beatrix Brooks

References

1:Block Museum

http://www.blockmuseum.northwestern.edu/view/exhibitions/current-exhibits/keep-the-shadow-ere-the-substance-fade-mourning-during-the-aids-crisis.html

2: History of HIV/AIDS

http://www.avert.org/professionals/history-hiv-aids/overview

3: Who was Etienne

http://www.leatherati.com/2009/11/who-was-etienne/

4: Etienne Leather Archives

http://www.leatherarchives.org/etienne.html

5: The Closet

http://theweek.com/articles/464753/where-did-phrase-come-closet-come-from

6: LGBTQ History Timeline

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_LGBT_history

7:Black Men in Leather Cain Berlinger

8:Urban Aboriginals Geoff Mains

9:Intersectionality

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kimberlé_Crenshaw

Author / curator : Erica Beatrix Brooks (Website , Facebook )

(c) Leather Archives & Museum. All Rights Reserved. No part of this website may be reproduced without the prior written permission of the Leather Archives & Museum, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

This project was made possible by a generous grant from the LGBT Fund of the Chicago Community Trust.